Out of Sight, Out of Mind

Perception of Dust The research set out to alter the contemporary perception of dust. The awareness and indispensability of air has long been explored. In the 19th century, the air was subject to mythical notions of miasma which held that smells from rotting organic matter was wrought with disease and epidemics. Consequently, whatever smelled bad was considered to be dangerous and harmful. But with the introduction of microscopes and visual technology, the invisible matter of dust came under intense inspection and germ theory replaced the miasma theory. Despite increased visibility into dust, attempts to categorize it have been divided. There are varied definitions and descriptions throughout different disciplines; some define it by size, distance travelled, or materiality. The World Health Organization currently summarizes as “solid particles, ranging in size from below 1 µm up to at least 100 µm, which may be or become airborne, depending on their origin, physical characteristics, and ambient conditions.” Dust can be further broken down into three subcategories. Nuisance dust or suspended particulates are any matter larger than 10 µm. Under “ideal” conditions, it takes them 10mins to drop in 6’ of height 100m. Inhalable dust or inert particulates are between 2.5 µm and 10 µm. 14.5 hours 250m. Respirable dust or fibrogenic particulates are smaller than 2.5 µm. 7 days 1km. The contemporary focus has been particularly on the smallest sizes of dust that can potentially infiltrate into the lungs, to which the exact effects on the body are still being researched. Nonetheless, dust is rarely talked about in material terms. The myth of cleaning renders dust unspecific, nothing definite. It achieves what Otero-Pailos calls ‘universality,’ since we are only able to conjure up very limited and banal images of dust. When the human eye can only see to about 40µm the perception of dust is a much subtler and less evident endeavor. We are still suddenly and unexpectedly disgusted by it.

Explication of Dust

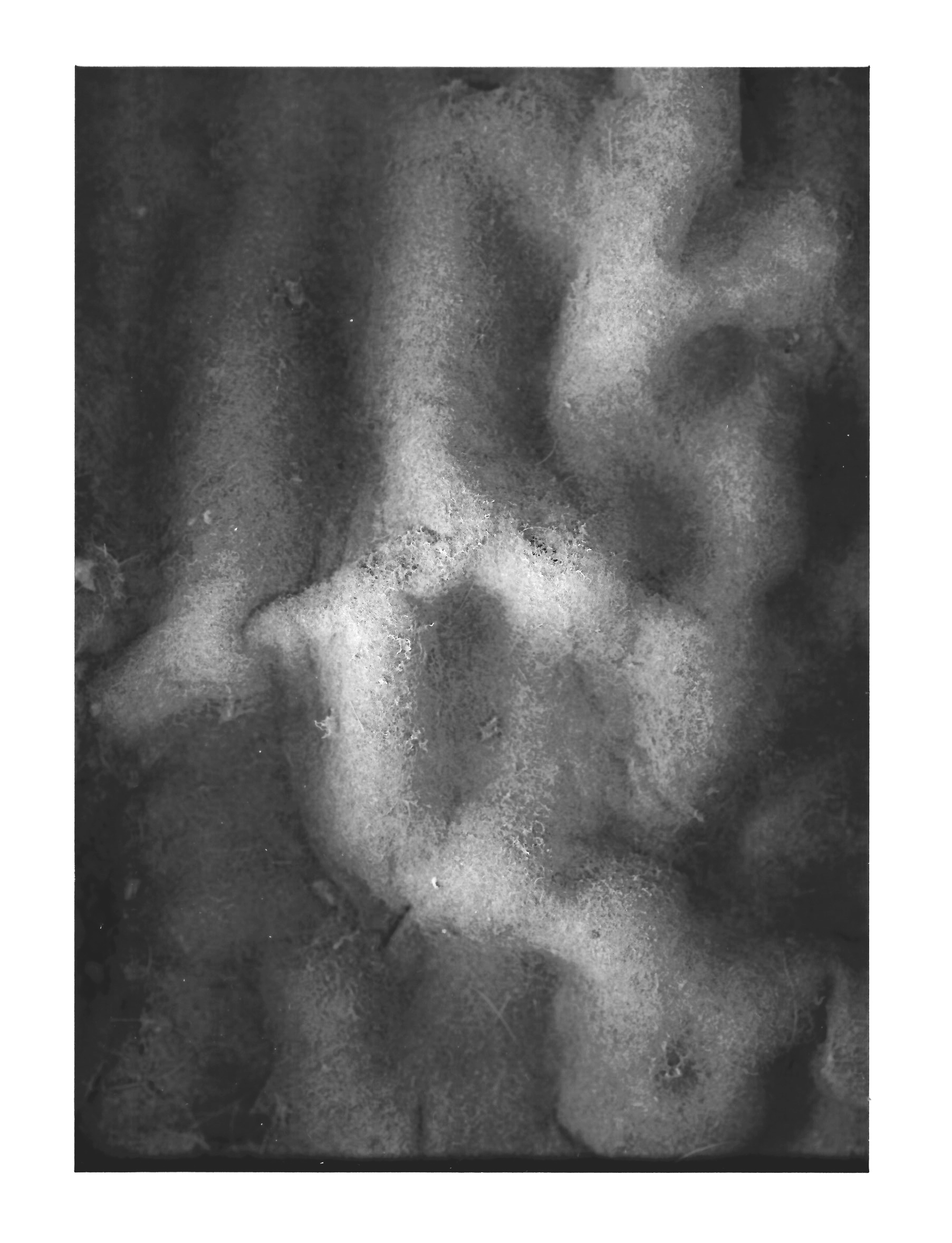

What exactly is dust? An extensive array of samples had been collected to view under various microscopes. However, the true origin and composition of the sample was inconclusive/untraceable. Reverse engineering the process and examining samples with known source emissions proved that different types of dust index related activities. Each and every movement of our daily routines, or minor acts of occupation, produces some form of dust- When you put on make-up, when you break bread, when you smoke, when you file your nails, when you shave, when you draw a line. And sometimes, we have no idea what it is. What constitutes dust cannot be simple/reductive, when it is very much a part of the human condition.

Absence of Dust

In the moment it took to read to this point, you have breathed about 43 times which equates to 0.75 cubic feet of air along with 0.0931g of dust. Dust seems ever pervasive but it is hard to imagine a place that is without it. The cleanroom is one such place. Lurie Nanofabrication Lab is where I have been working to image and understand the rigor of the ventilation system, using the SEM (Scanning Electron Microscope). The lab is an intensely filtrated environment with extremely low level of contaminants. Whilst the air we typically breathe contains around 35,000,000 particles per cubic meter, the highest level of cleanrooms have around 12 particles per cubic meter. Technically, without human activity this room might have zero contaminants. It is considered that the primary sources of contamination inside the rooms are from bodily regenerative processes, behavior, and attitude; all related to the user within. Sitting motionless generates 100,000 particles; swinging your arms produces 3,000,000 particles; walking at 3.5 mph, 7,000,000. Humans are the main emitters of dust and we must acknowledge the inhabitant’s role in producing it.

Deception/Presence of Dust, or the fallacy of cleanliness

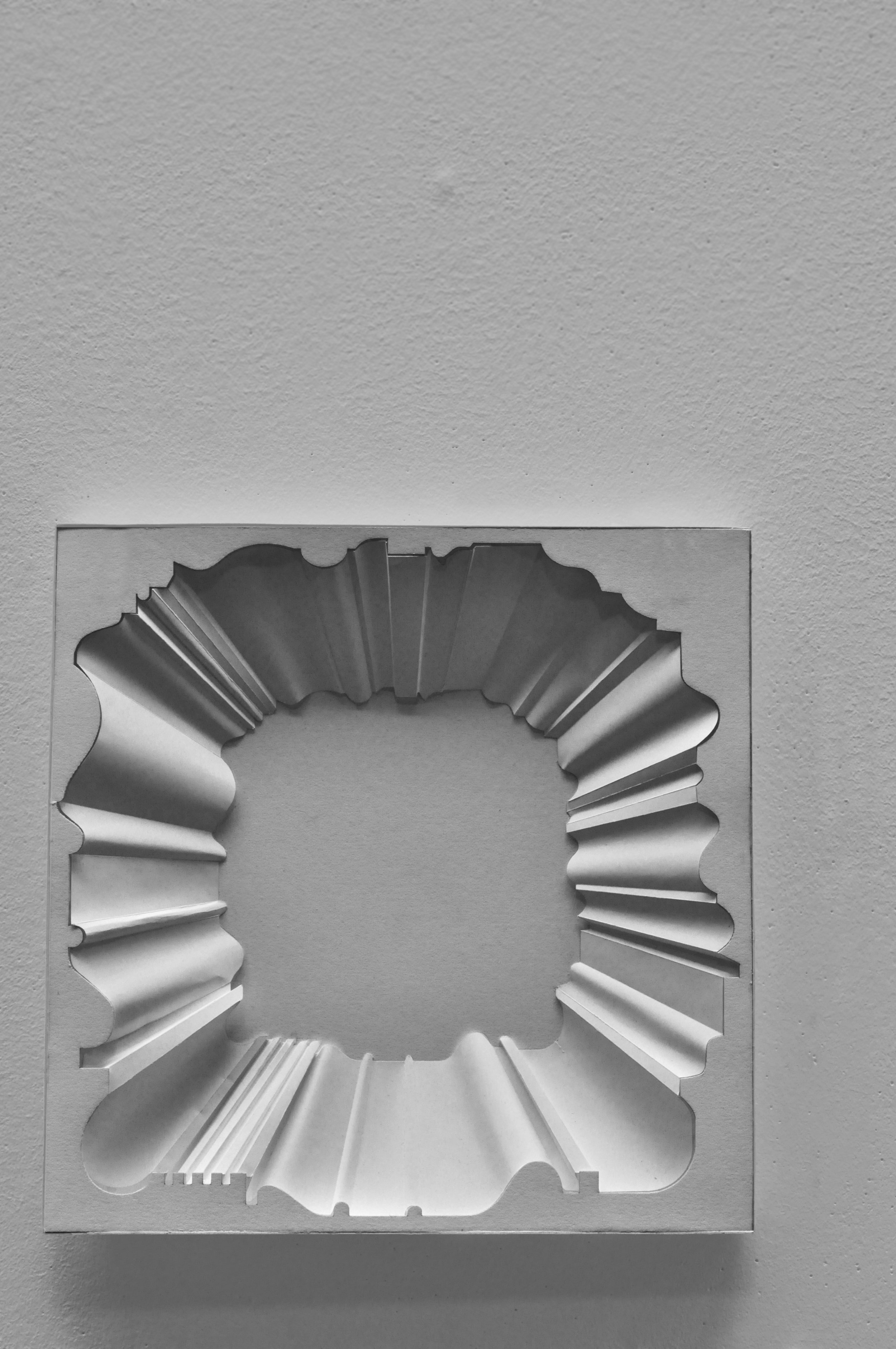

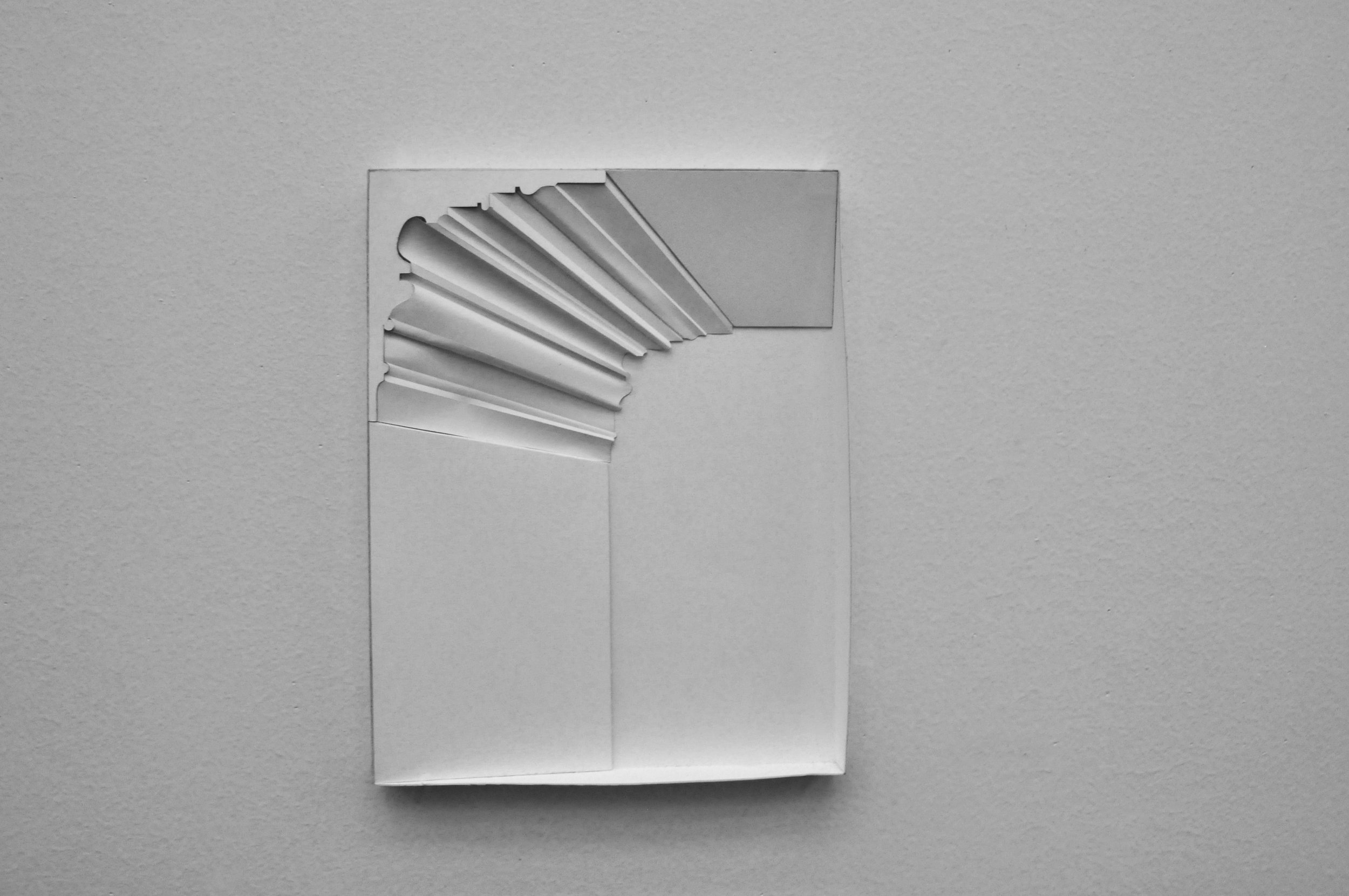

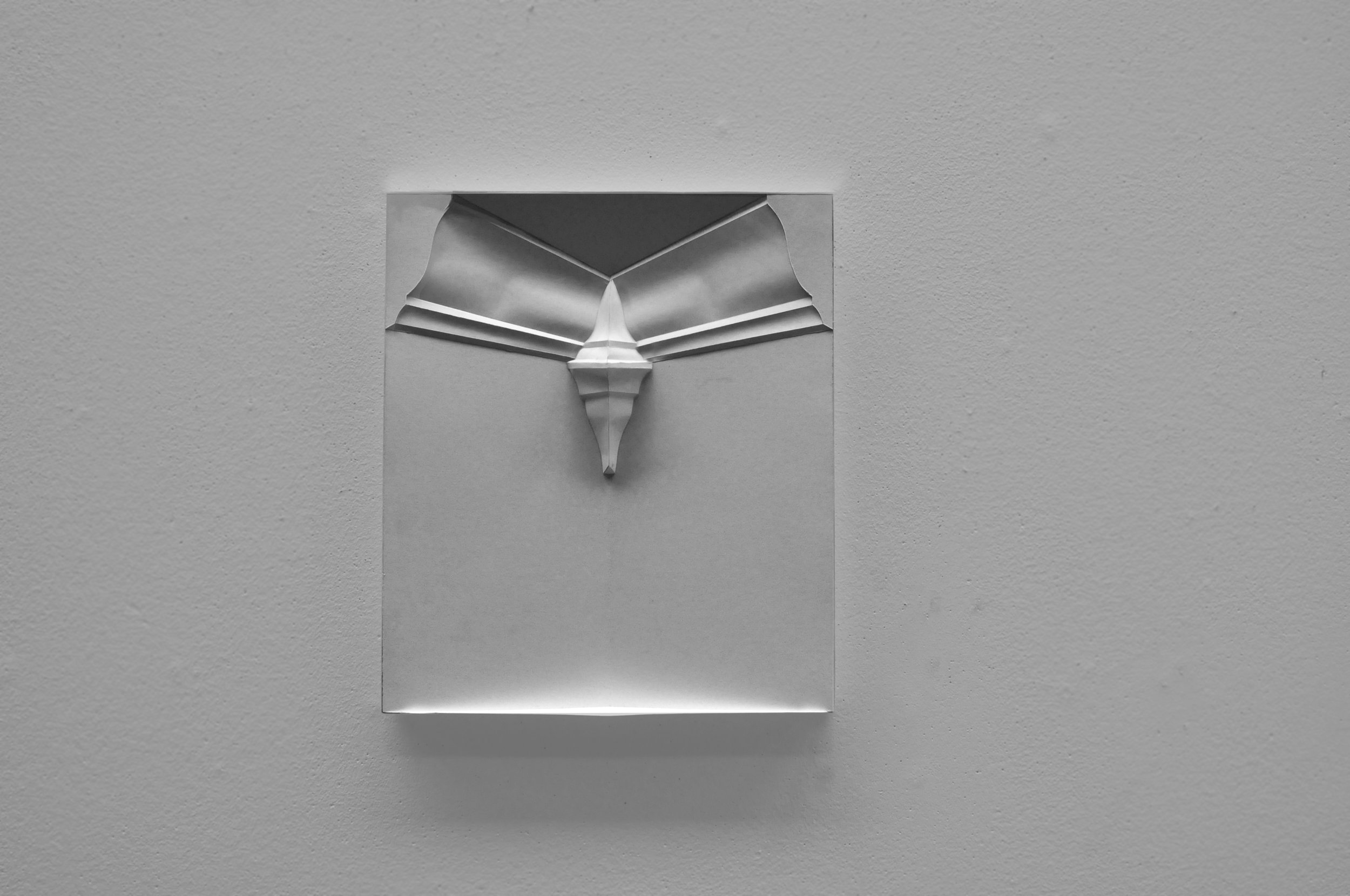

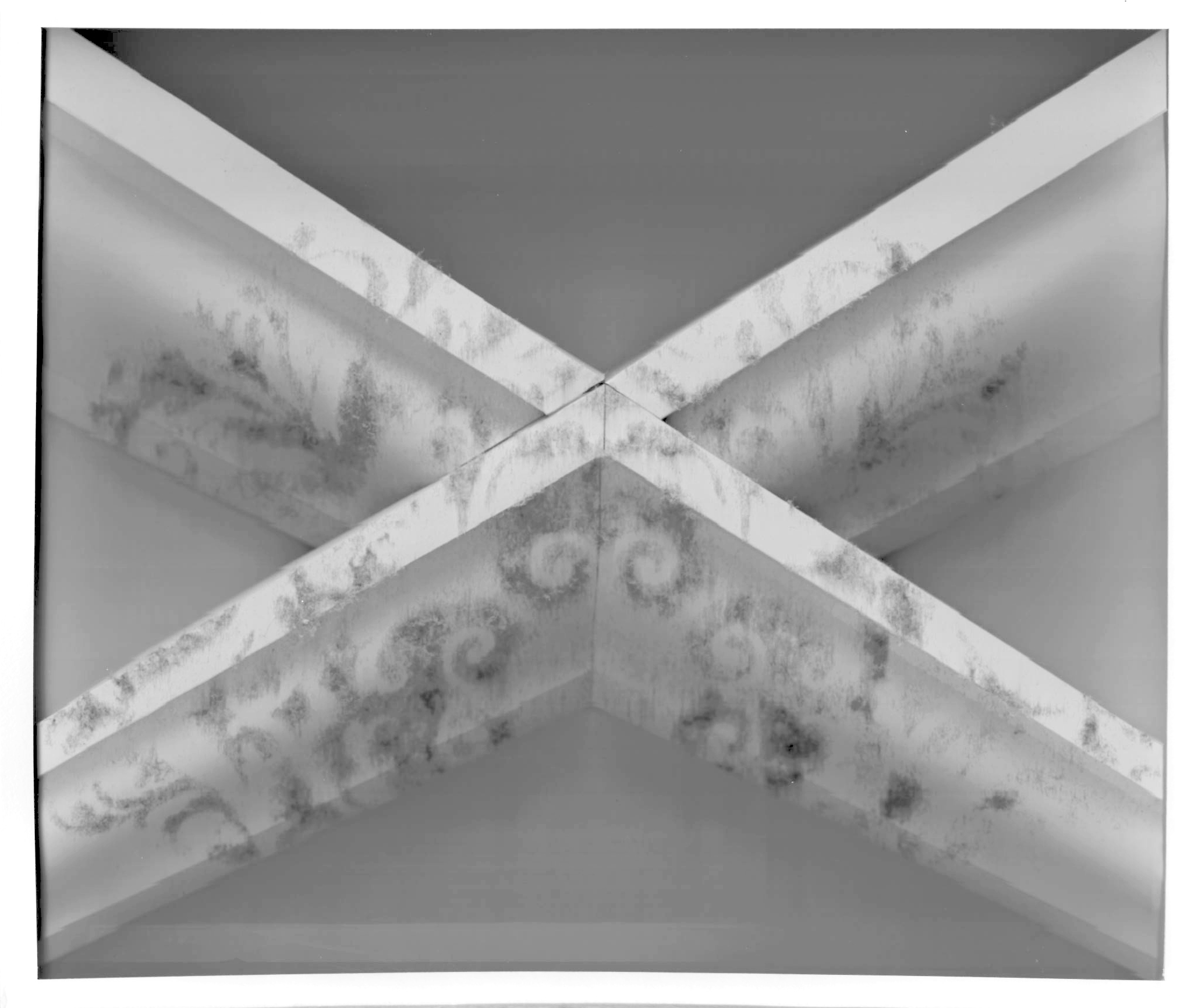

The investigations point to the fact that dust is never really “cleaned.” Critic Eileen Cleere, in Sanitary Arts, explores how new discoveries in the understanding of hygiene and cleanliness affected practices beyond public health, urban planning, and medicine; it also drastically changed the values of aesthetics. She highlights that visual preferences were sanitized and that “the ongoing work of sanitation reform in the nineteenth century was less concerned with mobilizing sophisticated technology of vision than with galvanizing the baser senses of the public to be more instinctively repulsed by dirt.” The Victorian domestic scene demonstrates how architects and their decorative elements joined the lineup of suspects that threatened health, hygiene, and cleanliness. Increasingly, carpets, curtains, cornices, decorative carvings, and the likes disappear from the home without considering the presence of lead or asbestos. Cleere also mentions the argument that the paranoia of dust may have been derived by “a desire to prevent the middle classes from encroaching upon decorative styles previously reserved for the upper class.” Industrial production had allowed the availability of affordable home décor. Many Victorian home decoration guides were meant to harness the potentially wayward tastes of untrained middle-class domestic designers, and the pedagogical mechanism used to produce aesthetic taste was often sanitation reform. Sanitation becomes an “imagined mechanism of social perfectibility;” scientific discovery and aesthetic values are not disparate forces of cultural influence anymore. The [mis]appropriation of scientific discoveries and their dissemination as common knowledge can become dangerously ingrained.

Attraction of Dust

Our apprehensions of dust are not without reason or evidence, but they are certainly misguided and flawed. It must be noted that health effects are specifically dependent upon composition, concentration, size and shape of particles, and exposure time. It is the trace amounts of asbestos or lead present in the air, not dust itself. Maintenance need not drive simplistic forms of cleaning, quarantine, and elimination- as David Gissen puts it, “engagement with pollution has resulted in the sublimation of architecture to a scientifically predetermined role and vision. Walls become layers of protection and filtration. Interior, as site of circulation where optimization of flows dominates. Architecture is both a refuge and a technical contraption to make pollution disappear as a thing and as an idea…Rather than a refuge from, architecture, becomes a context through which we come into contact with the degraded and amorphous historical matter.” The thesis set out to alter the contemporary perception of dust and reposition ourselves in terms of the distances we keep to it. They are considered to be signs of neglect but they are also signs of care and connection- of the things we irrationally keep. As much as they represent abandonment, they equally represent inhabitation. Rather than mere filth, they are conditions of age. It becomes offensive to our sensibilities only when it is “out of place” (Purity and Danger, Douglas).

Demiurge of Dust

To achieve this shift in perspective, clean and dirty had to be redefined. With regards to sanitation and health the antonym of ‘clean’ is now understood as toxic, noxious, and virulent. And to clean is to leave bare. If dirty/dusty is matter out of place, then broadly speaking, it means disorganized. How could the unassuming patterns of dust be registered in places we often neglect? Cosmos, from the Greek kosmos, means “order” and “arrangement,” while kosmein, the verb, means “to deck, adorn, or dress.” It was appropriate to return to the architectural ornament as an interface to incite and organize dust; to let it accumulate on expected places, as matter in place, in order to rid of the sudden and instantaneous nature of its visibility. Electrostatics can be used to attract dust onto surfaces and bodies. Van der Graaf generator and negative ion generators were used. Dust, as a material, can be molded, similar to how paper is made. All you require is a jig and some water. Fibrous dust can be twined in various ways to create a type of thread. Their tensile strength still needs to be tested. As a result, it can be braided. These three techniques were explored, some in more detail, to bolster and reiterate the symbolic value of a matter we commonly claim to know so much about. After all, what is dust, if not the salt from your tears or the graphite from the tip of your pencil? We depend heavily on dust.

Size of a Micron

Index of Dust Production

SEM Imaging done at Lurie Nanofabrication Lab of dust samples.